Children of the genocide

Lorraine Debnam describes how she used her chance to bring psychological help to Rwandan street children.

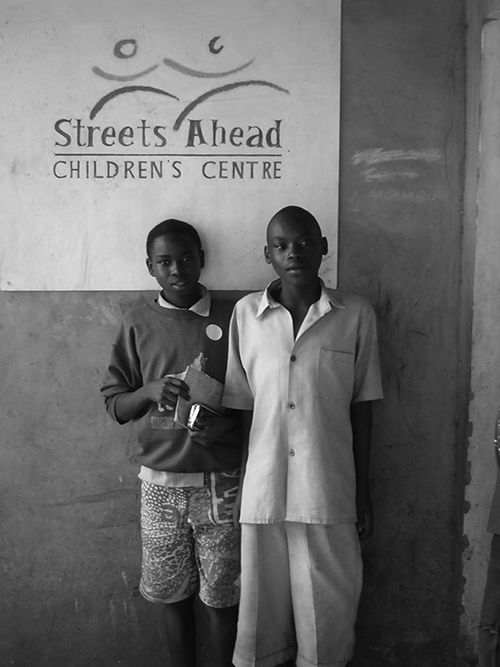

A generation of children in Rwanda is continuing to suffer the fallout from a nation so appalled by its own behaviour that it wants to forget the 1994 genocide ever happened. The street kids are an aspect of Rwanda that some financially successful Rwandans might like to ignore, but they aren’t going away, unless more people help them. Early last summer, my partner and I travelled to a town called Kayonza in eastern Rwanda to spend three weeks with a local charity that works with them, offering homes, education and a hope of change.

I heard about the children’s plight through a colleague in the child and adolescent mental health team where I work. Her vicar’s daughter Naomi and husband Mark had set up the charity, called the Street Ahead Children’s Centre Association (SACCA), after befriending young street kids while working as teachers with Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO). Starting from their own house and two sheds in the back garden, they now have six centres, in Kayonza, Rwamagana and Kabarondo, which they run with the Rwandan staff they have trained. In total, they care for about 170 young people and their babies.

All the young people are from splintered homes. Those over 14 were directly affected by the genocide. The younger ones are ‘secondary victims’: orphans whose parents died from AIDS, disease or starvation; children thrown out by new step-parents (when a Rwandan man remarries, his children take precedence over any children his new wife already has); young children forced to become ‘work horses’ for uncaring families (or abusive employers), who decided the streets would offer a better life; others just feel unable to live at home anymore – one young boy couldn’t bear to live next door to the man he had watched hack his father to death. On the streets, there is a growing drug and glue-sniffing culture (although drugs are illegal) and much petty crime among the children living disaffected, purposeless lives there.

We knew that we had physical jobs to do, such as building a courtyard in the boys’ centre in Kayonza and putting in drainage. But, because of my line of work, I had also been asked to help young people suffering bouts of depression and hopelessness for the future. I had lots of ideas, including skills and strategies from the human givens approach, and was keen to create as much positive change in three weeks as humanly possible. I eagerly set up a meeting with three lads, ranging in age from 14 to 20, and a translator (Speciose, then assistant manager at the centre and one of the principal carers or ‘teachers’ for the young adults and children). However, I soon realised that the meaning and intent behind language is not readily translatable. Also, translation of language does not translate cultural differences in power and expectations. The boys had been told that an English couple were coming out to help them. In England I might see that as my client already having hopeful expectations that I can assist. However, in Rwandan culture, it meant clients having to succeed and please the visitor, because I had come a long way and made a big effort. As a woman of 48 with greying hair (still youngish in UK culture!), I was “old, wise and deserved great respect”. The boys saw me as someone they had to be ‘good’ for and they tried very hard to say what they thought I expected them to say!

I couldn’t stop being a European white female. I had my own cultural beliefs, many of which I had never had to think about before and were hidden from me. So I decided that, in the short time I had available, the most important thing was to teach the ‘teachers’ something simple and effective, in keeping with their culture, that they, in turn, could pass on. I had initially had intentions of teaching the rewind technique. However, I had much support from my supervisor when I first started using it, whereas here, once I was gone, there would be extremely limited contact – just the chance of an occasional email when Mark visited Kigali, the capital, and managed to log on in an internet café. Relaxation and guided imagery, it seemed to me, would better meet the need.

The magic of storytelling

The ‘teachers’ I worked with had a varying command and comprehension of English. To avoid my earlier experience of meaning getting lost in translation, when explaining stress, I stopped talking about every 10 minutes for the group to catch up in their own language, clarify among themselves any misunderstanding and then summarise back to me. For visual aids to explain the fight and flight response, I drew pictures of animals on sheets of faded sugar paper on the floor of the room we were working in. The relaxation was done in the garden on blankets and rickety chairs.

It was during one of the first relaxation sessions that something serendipitous happened. I had taught the group to use guided imagery to help their ‘client’ enjoy the feelings of being in a quiet, safe, tranquil place. Speciose had helped Grace, (another ‘teacher’) relax so deeply that Grace had nearly relaxed out of her chair onto the dusty ground! While Grace was relaxed, Speciose had spontaneously told her a story that her grandfather used to tell. Afterwards, both the women remembered that, in their childhood, grandparents would tell stories to the children around the fire – traditional stories that taught the culture, beliefs and learning of a nation. Both the women recalled that, before the genocide, their own husbands and fathers had done the same, and how magical, hopeful and important the tradition had been. They decided that they were going to restart the tradition for the young people at the centres, inviting the elders to come in and tell stories for everyone to hear. The stories served as a reminder of a more peaceful time before the genocide and thus, in effect, gave them a vision and expectation of what life could be like again.

Stories which the group thought would help them to help themselves and others tended to be about leaving things behind that no longer worked or that were too heavy. Sometimes they were about burying items in a safe place, so they were not lost but safely hidden, climbing hills or being given new clothes. One man, Mbanda, had spoken only of “bad things”; while he was in a relaxed state, he was asked by his colleague if he would like to leave anything that was of no use to him behind in a safe place. When Mbanda ended his relaxation, he told us without any prompting that he had left a suitcase in a luggage locker in a large African railway station. He said that it was full of “bad things” and that he had never in his life felt so relieved, relaxed and happy to have been ‘allowed’ to leave it behind. The group had already understood the importance of metaphor in stories, but now they also understood it in a new way that they felt released them from painful memory patterns. It was amazing for me – an exhilarating experience, which brought me back to basics: uncomplicated interventions based on what works and is familiar to the clients.

Building confidence

Rwandan life is tough. Children work from a very young age: as soon as they can walk and carry water, they work for the family. Initiative and change are not encouraged and nurtured – people do what they are expected to do, which is what their fathers did. Adults also tend to talk negatively to children, picking up on their mistakes but not their achievements. I explained, as diplomatically as possible, the value of building confidence through positive observations and language (“I use this with the young people I work with in schools and find it really helps with their self-esteem”). When they related that to their own experiences as children and adults, they began to recognise there could be benefits. I also discussed with them the idea of letting young people reach their own decisions but that was unacceptable, as it seemed to them to undermine the traditional importance of adults passing on their greater experience.

During our visit the World Cup was on and, when England was playing, we few muzungos (white people) gathered with about a hundred African men in the ‘sports bar’, a breezeblock room with a big television on top of a box (television is watched only on very special occasions). At one point I sat back and observed. The room was full of excitement. All the men were over 18, which meant many would either have been victims of or witness to atrocities, and possibly some were perpetrators of those crimes.

Many survived by running away to neighbouring countries, using the fight or flight mechanism in the way it is meant to be used: for survival. Uganda, Tanzania and especially Congo expected refugees to work and perhaps this was a useful next stage, with no time to reflect on the trauma, no debriefing to reinforce the traumatic memory patterns. What I saw 12 years later amongst the ‘teachers’ (many of whom were returning refugees) was a group of determined, passionate people with a sense of purpose, belonging and love, who are giving hope to a generation that could so easily be lost in the struggle of rebuilding without scars.

The street kids of Rwanda are all a product of the genocide in one way or another, and I feel honoured to have had the chance to affect the lives of some of them in a small way. I treasure what Steven, a young man from Uganda who works for SACCA as a teacher, told me: “You must teach this to every teacher, every elder, everyone who cares. What we have learned has made so much difference to our lives that others must have it.”

For more information about SACCA, visit http://saccarwanda.org/

This article was first published in The Human Givens Journal Volume 14 - No. 3, 2007

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

Spread the word – each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. The journal takes no advertising at all, in order to maintain its editorial independence.

To survive, however, it needs new readers and subscribers – if you find the articles, case histories and interviews on this website helpful, and would like to support the human givens approach – please take out a subscription or buy a back issue today.

Latest Tweets:

Tweets by humangivensLatest News:

SCoPEd - latest update

The six SCoPEd partners have published their latest update on the important work currently underway with regards to the SCoPEd framework implementation, governance and impact assessment.

Date posted: 14/02/2024

2024 Conference

Our next in-person HGI Conference, is being held on the weekend of 20th and 21st April 2024